Mithraic Mysteries

The Mithraic Mysteries or Mysteries of Mithras (also Mithraism) was a mystery religion centered on the god Mithras, became popular among the military in the Roman Empire, from the 1st to 4th centuries AD. Information on the cult is based mainly on interpretations of the many surviving monuments. The most characteristic of these are depictions of Mithras as being born from a rock, and as sacrificing a bull. His worshippers had a complex system of seven grades of initiation, with ritual meals. They met in underground temples, which survive in large numbers. Little else is known for certain.

Contents |

Summary of the cult myth

Mithras is born from a rock.[1] He is depicted in his temples slaying a bull in the tauroctony (see section below). Little is known about the beliefs associated with this.[2] The ancient histories of the cult by Euboulos and Pallas have perished.[3] The name of the god was certainly given as Mithras (with an 's') in Latin monuments, although Mithra may have been used in Greek.[4]

History and development

Beginnings

In antiquity, texts refer to "the mysteries of Mithras", and to its adherents, as "the mysteries of the Persians."[5] But there is great dispute about whether there is really any link with Persia, and its origins are quite obscure.[6]

The mysteries of Mithras were not practiced until the 1st century AD.[7] The unique underground temples or Mithraea appear suddenly in the archaeology in the last quarter of the first century AD.[8]

Earliest cult locations

The attested locations of the cult in the earliest phase (c. 80–120 AD) are as follows:[9]

Mithraea datable from pottery

- Nida/Heddemheim III (Germania Sup.)

- Mogontiacum (Germania Sup.)

- Pons Aeni (Noricum)

- Caesarea (Judaea)

Datable dedications

- Nida/Heddernheim I (Germania Sup.) (CIMRM 1091/2, 1098)

- Carnuntum III (Pannonia Sup.) (CIMRM 1718)

- Novae (Moesia Inf.) (CIMRM 2268/9)

- Oescus(Moesia Inf.)(CIMRM 2250)

- Rome(CIMRM 362, 593/4)

Datable literary reference

- Rome (Statius, Theb. 1.719-20)

Earliest archaeology

The earliest Mithraic monument showing Mithras slaying the bull is thought to be CIMRM 593. This is a depiction of Mithras killing the bull, found in Rome. There is no date, but the inscription tells us that it was dedicated by a certain Alcimus, steward of T. Claudius Livianus. Vermaseren and Gordon believe that this Livianus is a certain Livianus who was commander of the Praetorian guard in 101 AD, which would give an earliest date of 98-99 AD.[10]

An altar or block from near SS. Pietro e Marcellino on the Esquiline in Rome was inscribed with a bilingual inscription by an Imperial freedman named T. Flavius Hyginus, probably between 80-100 AD. It is dedicated to Sol Invictus Mithras.[11]

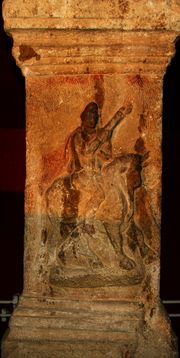

CIMRM 2268 is a broken base or altar from Novae/Steklen in Moesia Inferior, dated 100 AD, showing Cautes and Cautopates.

Other early archaeology includes the Greek inscription from Venosia by Sagaris actor probably from 100–150 AD; the Sidon cippus dedicated by Theodotus priest of Mithras to Asclepius, 140-141 AD; and the earliest military inscription, by C. Sacidius Barbarus, centurion of XV Apollinaris, from the bank of the Danube at Carnuntum, probably before 114 AD.[12]

The last is the earliest archaeological evidence outside Rome for the Roman worship of Mithras, a record of Roman soldiers who came from the military garrison at Carnuntum.[13] The earliest dateable Mithraeum outside Rome dates from 148 AD.[14] The Mithraeum at Caesarea Maritima is the only one in Palestine and the date is inferred.[15]

Vermaseren notes that no Mithraic monument can be certainly dated earlier than the end of the first century AD.[16]

Five small terracotta plaques of a figure holding a knife over a bull have been excavated near Kerch in the Crimea, dated by Beskow and Clauss to the second half of the first century BC,[17] and by Beck to 50 BC-50 AD, which might be a depiction of Mithras.[18] The bull-slaying figure wears a Phrygian cap, but is described by Beck and Beskow as otherwise unlike standard depictions of the tauroctony.[19]

Earliest literary references

The earliest surviving ancient literary text that can be associated with the Mysteries of Mithras is in Statius c. 80 AD, who makes an enigmatic reference, possibly to the tauroctony.[20] Dio Cassius, describing the visit of Tiridates to the emperor Nero in 63 AD, refers to his worshipping Mithras; but the context suggests that the Persian Mitra is intended.[21]

Origin Theories

Plutarch

The Greek biographer Plutarch (46 - 127) says that the pirates of Cilicia, the coastal province in the southeast of Anatolia, were the origin of the Mithraic rituals that were being practiced in Rome in his day: "They likewise offered strange sacrifices; those of Olympus I mean; and they celebrated certain secret mysteries, among which those of Mithras continue to this day, being originally instituted by them." (Life of Pompey 24, referring to events c. 68 BC). The 4th century commentary on Vergil by Servius says that Pompey settled some of these pirates in Calabria.[22] But whether any of this relates to the origins of the mysteries is unclear.[23]

Porphyry

According to 3-4th century AD philosopher Porphyry, Mithraists considered that their cult was founded by Zoroaster.[24] But Porphyry is writing close to the demise of the cult, and modern scholar Robert Turcan has challenged the idea that Porphyry's statements about Mithraism are accurate. His case is that far from representing what Mithraists believed, they are merely representations by the neo-platonists of what it suited them in the late 4th century to read into the mysteries.[25] Merkelbach and Beck believe that Porphyry's work "is in fact thoroughly coloured with the doctrines of the Mysteries."[26]

Cumont's hypothesis: possible origins in Persian Zoroastrianism

Scholarship on Mithras begins with Franz Cumont, who published a two volume collection of source texts and images of monuments in French in 1894–1900. Cumont's hypothesis, as the author summarizes it in the first 32 pages of his book, was that the Roman religion was "the Roman form of Mazdaism",[27] the Persian state religion, disseminated from the East.

Cumont's theories were examined and largely rejected at the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies held in 1971. John Hinnells was unwilling to reject entirely the idea of Iranian origin,[28] but wrote: "we must now conclude that his reconstruction simply will not stand. It receives no support from the Iranian material and is in fact in conflict with the ideas of that tradition as they are represented in the extant texts. Above all, it is a theoretical reconstruction which does not accord with the actual Roman iconography."[29] He discussed Cumont's reconstruction of the bull-slaying scene and stated "that the portrayal of Mithras given by Cumont is not merely unsupported by Iranian texts but is actually in serious conflict with known Iranian theology."[30] Another paper by R. L. Gordon argued that Cumont severely distorted the available evidence by forcing the material to conform to his predetermined model of Zoroastrian origins. Gordon suggested that the theory of Persian origins was completely invalid and that the Mithraic mysteries in the West was an entirely new creation.[31]

Boyce states that "no satisfactory evidence has yet been adduced to show that, before Zoroaster, the concept of a supreme god existed among the Iranians, or that among them Mithra - or any other divinity - ever enjoyed a separate cult of his or her own outside either their ancient or their Zoroastrian pantheons."[32]

Beck tells us that since the 1970s scholars have generally rejected Cumont, but adds that recent theories about how Zoroastrianism was during the period BC now makes some new form of Cumont's east-west transfer possible.[33] "Apart from the name of the god himself, in other words, Mithraism seems to have developed largely in and is, therefore, best understood from the context of Roman culture."[34]

Modern theories

Beck believes that the cult was created in Rome, by a single founder who had some knowledge of both Greek and Oriental religion, but suggests that some of the ideas used may have passed through the Hellenistic kingdoms: "Mithras — moreover, a Mithras who was identified with the Greek Sun god, Helios, ... was one of the deities of the syncretic Graeco-Iranian royal cult founded by Antiochus I, king of the small, but prosperous "buffer" state of Commagene, in the mid first century BC.[5]

Merkelbach suggests that its mysteries were essentially created by a particular person or persons[35] and created in a specific place, the city of Rome, by someone from an eastern province or border state who knew the Iranian myths in detail, which he wove into his new grades of initiation; but that he must have been Greek and Greek-speaking because he incorporated elements of Greek platonism into it. The myths, he suggests, were probably created in the milieu of the imperial bureaucracy, and for its members.[36] Clauss tends to agree. Beck calls this "the most likely scenario" and states "Till now, Mithraism has generally been treated as if it somehow evolved Topsy-like from its Iranian precursor -- a most implausible scenario once it is stated explicitly."[37]

Archaeologist Lewis M. Hopfe notes that there are only three Mithraea in Roman Syria, in contrast to further west. He writes: "archaeology indicates that Roman Mithraism had its epicenter in Rome... the fully developed religion known as Mithraism seems to have begun in Rome and been carried to Syria by soldiers and merchants."[38]

Taking a different view from most modern scholars, Ulansey argues that the Mithraic mysteries began in the Greco-Roman world as a religious response to the discovery by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus of the astronomical phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes — a discovery that amounted to discovering that the entire cosmos was moving in a hitherto unknown way. This new cosmic motion, he suggests, was seen by the founders of Mithraism as indicating the existence of a powerful new god capable of shifting the cosmic spheres and thereby controlling the universe.[39]

Ware asserted that the Romans who founded the cult borrowed the name "Mithras" from Avestan Mithra.[40]

Later History

The first important expansion of the mysteries in the Empire seems to have happened quite quickly, late in the reign of Antoninus Pius and under Marcus Aurelius. By this time all the key elements of the mysteries were in place.[41]

Mithraism reached the apogee of its popularity during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, spreading at an "astonishing" rate at the same period when Sol Invictus became part of the state cult.[42] At this period a certain Pallas devoted a monograph to Mithras, and a little later Euboulus wrote a History of Mithras, although both works are now lost.[43] According to the possibly spurious fourth century Historia Augusta, the emperor Commodus participated in its mysteries.[44] But it never became one of the state cults.[45]

The end of Mithraism

It is difficult to trace when the religion of Mithras came to an end. Beck states that "Quite early in the [fourth] century the religion was as good as dead throughout the empire."[46] Inscriptions from the fourth century are few. Clauss states that inscriptions show Mithras as one of the cults listed on inscriptions by pagan senators in Rome as part of the "pagan revival" among the elite.[47]

There is virtually no evidence for the continuance of the cult of Mithras into the fifth century. In particular large numbers of votive coins deposited by worshippers have been recovered at the Mithraeum at Pons Sarravi (Sarrebourg) in Gallia Belgica, in a series that runs from Gallienus (253-68) to Theodosius I (379-395). These were scattered over the floor when the Mithraeum was destroyed, as Christians apparently regarded the coins as polluted; and they therefore provide reliable dates for the functioning of the Mithraeum.[48] It cannot be shown that any Mithraeum continued in use in the fifth century. The coin series in all Mithraea end at the end of the fourth century at the latest. The cult disappeared earlier than that of Isis. Isis was still remembered in the middle ages as a pagan deity, but Mithras was already forgotten in late antiquity.[49]

Cumont stated in the English edition of his book that Mithraism may have survived in certain remote cantons of the Alps and Vosges into the fifth century, but the reference was only given in the French text, and was to the date of the coins in the Mithraeum at Pons Sarravi, none of which are in fact fifth century.[50]

Iconography

Much about Mithraism is only known from reliefs and sculptures. There have been many attempts to interpret this material.

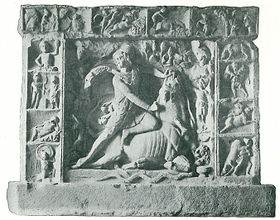

The tauroctony

In every Mithraeum the centrepiece was a representation of Mithras killing a sacred bull; the so-called tauroctony.[51]

The image may be a relief, or free-standing, and side details may be present or omitted. The centre-piece is Mithras clothed in Anatolian costume and wearing a Phrygian cap; who is kneeling on the exhausted [52] bull, holding it by the nostrils [52] with his left hand, and stabbing it with his right. As he does so, he looks over his shoulder towards the figure of Sol. A dog and a snake reach up towards the blood. A scorpion seizes the bull's genitals. The two torch-bearers are on either side, dressed like Mithras, Cautes with his torch pointing up and Cautopates with his torch pointing down.[53]

The event takes place in a cavern, into which Mithras has carried the bull, after having hunted it, ridden it and overwhelmed its strength [54] . Sometimes the cavern is surrounded by a circle, on which the twelve signs of the zodiac appear. Outside the cavern, top left, is Sol the sun, with his flaming crown, often driving a quadriga. A ray of light often reaches down to touch Mithras. Top right is Luna, with her crescent moon, who may be depicted driving a biga.

In some depictions, the central tauroctony is framed by a series of subsidiary scenes to the left, top and right, illustrating events in the Mithras narrative; Mithras being born from the rock, the water miracle, the hunting and riding of the bull, meeting Sol who kneels to him, shaking hands with Sol and sharing a meal of bull-parts with him, and ascending to the heavens in a chariot.

Sometimes Cautes and Cautopates carry shepherds' crooks instead.[55].

Interpretations and theories

Franz Cumont hypothesized that the imagery of the tauroctony was a Graeco-Roman representation of an event in Zoroastrian cosmogony described in a 9th century AD Zoroastrian text, the Bundahishn. In this text the evil spirit Ahriman (not Mithras) slays the primordial creature Gavaevodata which is represented as a bovine.[56] Cumont speculated that a version of the myth must have existed in which Mithras, not Ahriman, killed the bovine. But Hinnells points out that no such variant of the myth is known, and that this is merely speculation: "In no known Iranian text [either Zoroastrian or otherwise] does Mithra slay a bull" [57]

David Ulansey finds astronomical evidence from the mithraeum itself.[58] He reminds us that the Platonic writer Porphyry wrote in the 3rd century AD that the cave-like temple Mithraea depicted "an image of the world"[59] and that Zoroaster consecrated a cave resembling the world fabricated by Mithras[60] The ceiling of the Caesarea Maritima Mithraeum retains traces of blue paint, which may mean the ceiling was painted to depict the sky and the stars..[61]

Beck has given the following celestial anatomy of the Tauroctony:[62]

| Component of Tauroctony | Celestial Counterpart |

|---|---|

| Bull | Taurus |

| Dog | Canis Minor, Canis Major |

| Snake | Hydra, Serpens, Draco |

| Raven | Corvus |

| Scorpion | Scorpius |

| Wheat's ear (on bull's tail) | Spica |

| Twins Cautes and Cautopates | Gemini |

| Lion | Leo |

| Crater | Crater |

| Sol | Sun |

| Luna | Moon |

| Cave | Universe |

Several celestial identities for the Tauroctonous Mithras (TM) himself have been proposed. Beck summarizes them in the table below.[63]

| Scholar | Identification |

|---|---|

| Bausani, A. (1979) | TM associated with Leo, in that the tauroctony is a type of the ancient lion-bull (Leo-Taurus) combat motif. |

| Beck, R.L. (1994) | TM = Sun in Leo |

| Insler, S. (1978) | bull-killing = heliacal setting of Taurus |

| Jacobs, B. (1999) | bull-killing = heliacal setting of Taurus |

| North, J.D. (1990) | TM = Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) setting, his knife = Triangulum setting, his mantle = Capella (Alpha Aurigae) setting. |

| Rutgers, A.J. (1970) | TM = Sun, Bull = Moon |

| Sandelin, K.-G. (1988) | TM = Auriga |

| Speidel, M.P. (1980) | TM = Orion |

| Ulansey, D. (1989) | TM = Perseus |

| Weiss, M. (1994, 1998) | TM = the Night Sky |

Ulansey has proposed that Mithras seems to have been derived from the constellation of Perseus, which is positioned just above Taurus in the night sky. He sees iconographic and mythological parallels between the two figures: both are young heroes, carry a dagger and wear a Phrygian cap. He also mentions the similarity of the image of Perseus killing the Gorgon and the tauroctony, both figures being associated with underground caverns and both having connections to Persia as further evidence.[64]

Michael Speidel associates Mithras with the constellation of Orion because of the proximity to Taurus, and the consistent nature of the depiction of the figure as having wide shoulders, a garment flared at the hem, and narrowed at the waist with a belt, thus taking on the form of the constellation.[65]

Beck has criticized Speidel and Ulansey of adherence to a literal cartographic logic, describing their theories as a "will-o'-the-whisp" which "lured them down a false trail."[66] He argues that a literal reading of the tauroctony as a star chart raises two major problems: it is difficult to find a constellation counterpart for Mithras himself (despite efforts by Speidel and Ulansey) and that unlike in a star chart, each feature of the tauroctony might have more than a single counterpart. Rather than seeing Mithras as a constellation, Beck argues that Mithras is the prime traveller on the celestial stage (represented by the other symbols of the scene), the Unconquered Sun moving through the constellations.[66]

The banquet

The second most important scene after the tauroctony in Mithraic art is the so-called banquet scene.[67] The two scenes are sometimes sculpted on the opposite sides of the same relief. The banquet scene features Mithras and the Sun god banqueting on the hide of the slaughtered bull [67]. On the specific banquet scene on the Fiano Romano relief (see image on the right), one of the torchbearers points a caduceus towards the base of an altar, where flames appear to spring up. Robert Turcan has argued that since the caduceus is an attribute of Mercury, and in mythology Mercury is depicted as a psychopompos, the eliciting of flames in this scene is referring to the dispatch of human souls and expressing the Mithraic doctrine on this matter.[68] Turcan also connects this event to the tauroctony: the blood of the slayed bull has soaked the ground at the base of the altar, and from the blood the souls are elicited in flames by the caduceus.[68]

Leontocephaline

One of the most characteristic features of the Mysteries is the naked lion-headed figure often found in Mithraic temples. He is entwined by a serpent, with the snake's head often resting on the lion's head. The lion's mouth is often open, giving a horrifying impression. He is usually represented having four wings, two keys (sometimes a single key) and a scepter in his hand. Sometimes the figure is standing on a globe inscribed with a diagonal cross. A more scarcely represented variant of the figure with a human head is also found.[69]

Although animal-headed figures are prevalent in contemporary Egyptian and Gnostic mythological representations, the Leontocephaline is entirely restricted to Mithraic art.[69]

The name of the figure has been deciphered from dedicatory inscriptions to be Arimanius (though the archeological evidence is not very strong), which is nominally the equivalent of Ahriman, a demon figure in the Zoroastrian pantheon. Arimanius is known from inscriptions to have been a deus in the Mithraic cult (CIMRM 222 from Ostia, 369 from Rome, 1773 and 1775 from Pannonia) [70]

Although the exact identity of the lion-headed figure is debated by scholars, it is largely agreed that the god is associated with time and seasonal change.[71]

The Taurobolium

No ancient source associates Mithras with the Taurobolium. The only monument to do so, CIL VI, 736, is a forgery.[72]

Rituals and worship

Little is known about the beliefs of the cult of Mithras. Modern accounts rely primarily on modern interpretation of the reliefs.[2]

No Mithraic scripture or first-hand account of its highly secret rituals survives, with the possible exception of a liturgy recorded in a 4th century papyrus, which may not be Mithraic at all.[73] The walls of Mithraea were commonly whitewashed, and where this survives it tends to carry extensive repositories of graffiti; and these, together with inscriptions on Mithraic monuments, form the main source for Mithraic texts [74] .

Nevertheless, it is clear from the archeology of numerous Mithraea that most rituals were associated with feasting - as eating utensils and food residues are almost invariably found. These tend to include both animal bones and also very large quantities of fruit residues.[75] The presence of large amounts of cherry-stones in particular would tend to confirm mid-summer (late June, early July) as a season especially associated with Mithraic festivities. The Virunum album, in the form of an inscribed bronze placque, records a Mithraic festival of commemoration as taking place on 26 June 184. Beck argues that religious celebrations on this date are indicative of special significance being given to the Summer solstice; but equally it may well be noted that, in northern and central Europe, reclining on a masonry plinth in an unheated cave was likely to be a predominantly summertime activity. For their feasts, Mithraic initiates reclined on stone benches arranged along the longer sides of the Mithraeum - typically there might be room for 15-30 diners, but very rarely many more than 40.[76] Counterpart dining rooms, or triclinia were to be found above ground in the precints of almost any temple or religious sanctuary in the Roman empire, and such rooms were commonly used for their regular feasts by Roman 'clubs', or collegia. Mithraic feasts probably performed a very similar function for Mithraists as the collegia did for those entitled to join them; indeed, since qualification for Roman collegia tended to be restricted to particular families, localities or traditional trades, Mithraism may have functioned in part as providing clubs for the unclubbed.[77]

Each Mithraeum invariably had several altars at the further end, underneath the representation of the tauroctony; and also commonly contained considerable numbers of subsidiary altars, both in the main Mithraeum chamber, and in the ante-chamber or narthax.[78] These altars, which are of the standard Roman pattern, each carry a named dedicatory inscription from a particular initiate, who dedicated the altar to Mithras "in fulfillment of his vow", in gratitude for favours received. Burned residues of animal entrails are commonly found on the main altars indicating regular sacrificial use. However, Mithraea do not commonly appear to have been provided with facilities for ritual slaughter of sacrificial animals (a highly specialised function in Roman religion), and it may be presumed that a Mithraeum would have made arrangements for this service to be provided for them in co-operation with the professional victimarius[79] of the civic cult.

Mithraic beliefs appear not to have been internally consistent and monolithic,[80] but rather, varied from location to location.[81] Mithraism had no predominant sanctuary or cultic centre; and, although each Mithraeum had its own officers and functionaries, there was no central supervisory authority. In some Mithraea, such as that at Dura Europos wall paintings depict prophets carrying scrolls[82], but no named Mithraic sages are known, nor does any reference give the title of any Mithraic scripture or teaching. It is known that intitates could transfer with their grades from one Mithraeum to another[83], but we do not know how a Mithraeum could tell who was properly an initiate (or indeed whether this was ever an issue; as it most certainly was in contemporary Christianity).

The mithraeum

Temples of Mithras are sunk below ground, windowless, and very distinctive. In cities, the basement of an apartment block might be converted; elsewhere they might be excavated and vaulted over, or converted from a natural cave. Mithraic temples are common in the empire; although very unevenly distributed, with considerable numbers found in Rome, Ostia, Numidia, Dalmatia, Britain and along the Rhine/Danube frontier; while being much less common in Greece, Egypt, and Syria [84] . Mithriac rituals being secret, Mithraism could only be practiced within a Mithraeum [85]; and consequently it may be safely concluded that areas without Mithraea were also without Mithraists. More than 420 Mithraic sites have now been identified [86]. By their nature Mithraea tend to survive when other forms of religious structures do not; and consequently the relative prevalence of Mithraism in the population may well tend to be over-estimated. For the most part, Mithraea tend to be small, externally undistinguished, and cheaply constructed; the cult generally preferring to create a new centre rather than expand an existing one. The Mithraeum represented the cave in which Mithras carried and then killed the bull; and where stone vaulting could not be afforded, the effect would be imitated with lath and plaster. They are commonly located close to springs or streams; fresh water appears to have been required for some Mithraic rituals, and a basin is often incorporated into the structure [87] . There is usually a narthax or ante-chamber at the entrance, and often other ancillary rooms for storage and the preparation of food. The term mithraeum is modern; in Italy inscriptions usually call it a spelaeum; outside Italy it is referred to as templum.

In their basic form, Mithraea were entirely different from the temples and shrines of other cults. In standard pattern Roman religious precincts, the temple building functioned as a house for the God; who was intended to be able to view through the opened doors and columnar portico, sacrificial worship being offered on an altar set in an open courtyard; potentially accessible not only to initiates of the cult, but also to colitores or non-initiated worshippers [88]. Mithraea were the antithesis of this [89]; being entirely inward-focussed with altars set within the building, and with no sacred precinct, or indeed any provision for worshippers other than initates. .

Degrees of initiation

In the Suda under the entry "Mithras", it states that "no one was permitted to be initiated into them (the mysteries of Mithras), until he should show himself holy and steadfast by undergoing several graduated tests."[90] Gregory Nazianzen refers to the "tests in the mysteries of Mithras".[91]

There were seven grades of initiation into the mysteries of Mithras, which are listed by St. Jerome[92]. Manfred Clauss states that the number of grades, seven, must be connected to the planets. A mosaic in the Ostia Mithraeum of Felicissimus depicts these grades, with heraldic emblems that are connected either to the grades or are just symbols of the planets. The grades also have an inscription besides them commending each grade into the protection of the different planetary gods.[93] In ascending order of importance the initiatory grades were:[94]

| Grade | Symbols | Associated planet/Protecting deity |

|---|---|---|

| Corax (raven) | beaker, caduceus | Mercury |

| Nymphus (bridegroom, or male bride) | lamp, diadem | Venus |

| Miles (soldier) | pouch, helmet, lance | Mars |

| Leo (lion) | batillum, sistrum, thunderbolts | Jupiter |

| Perses (Persian) | akinakes, scythe, moon and the stars | Luna |

| Heliodromus (sun-runner) | torch, radiated crown, whip | Sol |

| Pater (father) | patera (or ring?), staff, Phrygian cap, sickle | Saturn |

Elsewhere, as at Dura Europos Mithraic graffiti survive giving membership lists, in which initiates of a Mithraeum are named with their Mithraic grades. At Virunum, the membership list or album sacratorum was maintained as an inscribed plaque, updated year by year as new members were initiated. By cross-referencing these lists it is sometimes possible to track initiates from one Mithraeum to another; and also speculatively to identify Mithraic initiates with persons on other contemporary lists - such as military service rolls, of lists of devotees of non-Mithraic religious sanctuaries. Names of initiates are also found in the dedication inscriptions of altars and other cult objects. Clauss noted in 1990 that overall, only about 14% of Mithriac names inscribed before 250 identify the initiates grade - and hence questioned that the traditional view that all initiates belonged to one of the seven grades [95]. Clauss argues that the grades represented a distinct class of priests, sacerdotes. Gordon maintains the former theory of Merkelbach and others, especially noting such examples as Dura where all names are associated with a Mithraic grade. Some scholars maintain that practice may have differed over time, or from one Mithraea to another.

The highest grade, pater, is far the most common found on dedications and inscriptions - and it would appear not to have been unusual for a Mithraeum to have several persons with this grade. The form pater patrum (father of fathers) is often found, which appears to indicate the pater with primary status. There are several examples of persons, commonly those of higher social status, joining a Mithraeum with the status pater - especially in Rome during the 'pagan revival' of the fourth century. It has been suggested that some Mithraea may have awarded honorary pater status to sympathetic dignitaries [96].

The initiate into each grade appears to have required to undertake a specific ordeal or test [97] , involving exposure to heat, cold or threatened peril. An 'ordeal pit', dating to the early 3rd century, has been identified in the Mithraeum at Carrawburgh. Accounts of the cruelty of the emperor Commodus describes his amusing himself by enacting Mithriac initiation ordeals in homicidal form. By the later 3rd century, the enacted trials appear to have been abated in rigor, as 'ordeal pits' were floored over.

Admission into the community was completed with a handshake with the pater, just as Mithras and Sol shook hands. The initiates were thus referred to as syndexioi, those "united by the handshake". The term is used in an inscription by Proficentius [98] and derided by Firmicus Maternus [99]

Ritual imitations

Activities of the most prominent deities in Mithraic scenes, Sol and Mithras, were imitated in rituals by the two most senior officers in the cult's hierarchy, the Pater and the Heliodromus.[100]. The initiates held a sacramental banquet, replicating the feast of Mithras and Sol.[100]

Reliefs on a cup found in Mainz,[101][102] appear to depict a Mithraic initiation. On the cup, the initiate is depicted as led into a location where a Pater would be seated in the guise of Mithras with a drawn bow. Accompanying the initiate is a mystagogue, who explains the symbolism and theology to the initiate. The Rite is thought to re-enact what has come to be called the 'Water Miracle', in which Mithras fires a bolt into a rock, and from the rock now spouts water.

Roger Beck has hypothesized a third processional Mithraic ritual, based on the Mainz cup and Porphyrys. This so-called Procession of the Sun-Runner features the Heliodromus, escorted by two figures representing Cautes and Cautopates (see below) and preceded by an initiate of the grade Miles leading a ritual enactment of the solar journey around the mithraeum, which was intended to represent the cosmos.[103]

Consequently it has been argued that most Mithraic rituals involved a re-enactment by the initiates of episodes in the Mithras narrative [104], a narrative whose main elements were; birth from the rock, striking water from stone with an arrow shot, the killing of the bull, Sol's submission to Mithras, Mithras and Sol feasting on the bull, the ascent of Mithras to heaven in a chariot. A noticeable feature of this narrative (and of its regular depiction in surviving sets of relief carvings) is the complete absence of female personages [105]. Mithras has no mother, consort or children. As a form of mutual religious courtesy Mithraea commonly also hosted statues to non-Mithraic divinities, and feminine gods were not excluded from this, but in the main Mithraic iconographic sequence only the figure of Luna is presented as feminine, and she is not depicted as interacting with Mithras or participating in the action of the narrative in any way.

From this, and from the evidence of membership lists, it is generally believed that the cult was for men only. It has recently been suggested by one scholar that "women were involved with Mithraic groups in at least some locations of the empire."[106] Soldiers were strongly represented amongst Mithraists; and also merchants, customs officials and minor bureaucrats. Few, if any, initiates came from leading aristocratic or senatorial families until the 'pagan revival' of the mid 4th century; but there were always considerable numbers of freedmen and slaves .[107].

Mithraic Ethics

Clauss suggests that a statement by Porphyry that people initiated into the Lion grade must keep their hands pure from everything that brings pain and harm and is impure means that moral demands were made upon members of congregations.[108]. A passage in the Caesares of Julian the Apostate refers to "commandments of Mithras".[109]Tertullian, in his treatise 'On the Military Crown' records that Mithraists in the army were officially excused from wearing celebratory coronets; on the basis that the Mithraic initiation ritual included refusing a proffered crown, because "their only crown was Mithras" [110].

Mithras and other gods

Syncretism was a feature of Roman paganism, and the cult of Mithras was part of this. Almost all Mithraea contain statues dedicated to gods of other cults, and it is common to find inscriptions dedicated to Mithras in other sanctuaries, especially those of Jupiter Dolichenus [111] . Mithraism was not an alternative to other pagan religions, but rather a particular way of practising pagan worship; and many Mithraic initiates can also be found worshipping in the civic religion, and as initiates of other mystery cults [112]. Although modern scholarship refers to Mithraic initiates as Mithraists, no equivalent term is found in antique Mithraic texts; Mithraic congregations appear to have needed no general term to distinguish their own members.

Mithraism and Christianity

The idea of a relationship between early Christianity and Mithraism is based on a remark in the 2nd century Christian writer Justin Martyr, who accused the Mithraists of diabolically imitating the Christian communion rite.[113] Based upon this, Ernest Renan in 1882 set forth a vivid depiction of two rival religions: "if the growth of Christianity had been arrested by some mortal malady, the world would have been Mithraic,"[114] Edwin M. Yamauchi comments on Renan's work which, "published nearly 150 years ago, has no value as a source. He [Renan] knew very little about Mithraism..."[115]

References

- ↑ Commodian, Instructiones 1.13: "The unconquered one was born from a rock, if he is regarded as a god."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Clauss, M. The Roman cult of Mithras, p. xxi: "we possess virtually no theological statements either by Mithraists themselves or by other writers."

- ↑ Porphyry, De Antro Nympharum tells us of both writers.

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L. (1978). "The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection". Journal of Mithraic Studies II: 148–174.. p. 160: "The usual western nominative form of Hithras' name in the mysteries ended in -s, as we can see from the one authentic dedication in the nominative, recut over a dedication to Sarapis (463, Terme de Caracalla), and from occasional grammatical errors such as deo inviato Metras (1443). But it is probable that Euboulus and Pallas at least used the name Mithra as an indeclinable (ap. Porphyry, De abstinentia II.56 and IV.16)."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beck, Roger (2002). "Mithraism". Encyclopædia Iranica. Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/sup/Mithraism.html. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ See detailed discussion of possible origins below.

- ↑ Clauss, Manfred (2000). Gordon, Richard (trans.). ed. The Roman cult of Mithras. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 074861396X.

- ↑ Beck, R., “The Mysteries of Mithras: A New Account of their Genesis”, Journal of Roman Studies, 1998, 115-128. p. 118.

- ↑ "Beck on Mithraism", pp. 34–35. Online here.

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L. (1978). "The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection". Journal of Mithraic Studies II: 148–174.. Online here.

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L. (1978). "The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection". Journal of Mithraic Studies II: 148–174.. Online here CIMRM 362 a , b = el l, VI 732 = Moretti, lGUR I 179: "Soli | Invicto Mithrae | T . Flavius Aug. lib. Hyginus | Ephebianus | d . d." - but the Greek title is just "`Hliwi Mithrai". The name "Flavius" for an imperial freedman dates it between 70-136 AD. The Greek section refers to a pater of the cult named Lollius Rufus, evidence of the existence of the rank system at this early date.

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L. (1978). "The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection". Journal of Mithraic Studies II: 148–174. p. 150.

- ↑ C. M. Daniels, "The Roman army and the spread of Mithraism" in John R. Hinnels, Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, vol. 2, 1975, Manchester UP, pp.249-274. "The considerable movement [of civil servants and military] throughout the empire was of great importance to Mithraism, and even with the very fragmentary and inadequate evidence that we have it is clear that the movement of troops was a major factor in the spread of the cult. Traditionally there are two geographical regions where Mithraism first struck root: Italy and the Danube. Italy I propose to omit, as the subject needs considerable discussion, and the introduction of the cult there, as witnessed by its early dedicators, seems not to have been military. Before we turn to the Danube, however, there is one early event (rather than geographical location) which should perhaps be mentioned briefly in passing. This is the supposed arrival of the cult in Italy as a result of Pompey the Great's defeat of Cicilian pirates, who practiced 'strange sacrifices of their own... and celebrated certain secret rites, amongst which those of Mithras continue to the present time, have been first instituted by them'. (ref Plutarch, "Pompey" 24-25) Suffice it to say that there is neither archaelogical nor allied evidence for the arrival of Mithraism in the west at that time, nor is there any ancient literary reference, either contemporary or later. If anything, Plutarch's mention carefully omits making the point that the cult was introduced into Italy at that time or by the pirates. Turning to the Danube, the earliest dedication from that region is an altar to Mitrhe (sic) set up by C. Sacidus Barbarus, a centurion of XV Appolinaris, stationed at the time at Carnuntum in Pannonia (Deutsch-Altenburg, Austria). The movements of this legion are particularly informative." The article then goes on to say that XV Appolinaris was originally based at Carnuntum, but between 62-71 transferred to the east, first in the Armenian campaign, and then to put down the Jewish uprising. Then 71- 86 back in Carnuntum, then 86-105 intermittently in the Dacian wars, then 105-114 back in Carnuntum, and finally moved to Cappadocia in 114.

- ↑ C. M. Daniels, "The Roman army and the spread of Mithraism" in John R. Hinnels, Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, vol. 2, 1975, Manchester UP, p. 263. The first dateable Mithraeum outside italy is from Böckingen on the Neckar, where a centurion of the legion VIII Augustus dedicated two altars, one to Mithras and the other (dated 148) to Apollo.

- ↑ Lewis M. Hopfe, "Archaeological indications on the origins of Roman Mithraism", in Lewis M. Hopfe (ed). Uncovering ancient stones: essays in memory of H. Neil Richardson, Eisenbrauns (1994), pp. 147-158. p.153: "At present this is the only Mithraeum known in Roman Palestine." p. 154: "It is difficult to assign an exact date to the founding of the Caesarea Maritima Mithraeum. No dedicatory plaques have been discovered that might aid in the dating. The lamps found with the taurectone medallion are from the end of the first century to the late third century A.D. Other pottery and coins from the vault are also from this era. Therefore it is speculated that this Mithraeum developed toward the end of the first century and remained active until the late third century. This matches the dates assigned to the Dura-Europos and the Sidon Mithraea."

- ↑ Vermaseren, M.J., Mithras: the Secret God, p. 29: "One other point of note is that no Mithraic monument can be dated earlier than the end of the first century AD, and even the more extensive investigations at Pompeii, buried beneath the ashes of Vesuvius in AD 79, have not produced a single image of the god."

- ↑ Beskow, Per, The routes of early Mithraism, in Études mithriaques Ed.Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin. p.14: "Another possible piece of evidence is offered by five terracotta plaques with a tauroctone, found in Crimea and taken into the records of Mithraic monuments by Cumont and Vermaseren. If they are Mithraic, they are certainly the oldest known representations of Mithras tauroctone; the somewhat varying dates given by Russian archaeologists will set the beginning of the first century C.E. as a terminus ad quem, which is also said to have been confirmed by the stratigraphic conditions." Note 20 gives the publication as W. Blawatsky / G. Kolchelenko, Le culte de Mithra sur la cote spetentrionale de la Mer Noire, Leiden 1966, p.14f. See also Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.156-7 which merely mentions the date and presumes that the deity is Mithras-Attis.

- ↑ ...the area [the Crimea] is of interest mainly because of the terracotta plaques from Kerch (five, of which two are in CIMRM as nos 11 and 12). These show a bull-killing figure and their probable date (second half of first-century BC to first half of first AD) would make them the earliest tauroctonies -- if it is Mithras that they portray. Their iconography is significantly different from that of the standard tauroctony (e.g. in the Attis-like exposure of the god's genitals). Roger Beck, Mithraism since Franz Cumont, Aufsteig und Niedergang der romischen Welt II 17.4 (1984), p. 2019

- ↑ Beskow continues: "The plaques are typical Bosporan terracottas... At the same time it must be admitted that the plaques have some strange features which make it debateable if this is really Mithra(s). Most striking is the fact that his genitals are visible as they are in the iconography of Attis, which is accentuated by a high anaxyrides. Instead of the tunic and flowing cloak he wears a kind of jacket, buttoned over the breast with only one button, perhaps the attempt of a not so skillful artist to depict a cloak. The bull is small and has a hump and the tauroctone does not plunge his knife into the flank of the bull but holds it lifted. The nudity gives it the character of a fertility god and if we want to connect it directly with the Mithraic mysteries it is indeed embarrassing that the first one of these plaques was found in a woman's tomb." Roger Beck, Mithraism since Franz Cumont, Aufsteig und Niedergang der romischen Welt II 17.4 (1984), p. 2019: "Their iconography is significantly different from that of the standard tauroctony (e.g. in the Attis-like exposure of the god's genitals)." Clauss, p.156: "He is grasping one of the bull's horns with his left hand, and wrenching back its head; the right arm is raised to deliver the death-blow. So far, this god must be Mithras. But in sharp contrast with the usual representations, he is dressed in a jacket-like garment, fastened at the chest with a brooch, which leaves his genitals exposed - the iconography typical of Attis."

- ↑ Statius, Thebaid (Book i. 719,720): "Mithras twists the unruly horns beneath the rocks of a Persian cave."

- ↑ Dio, Cassius, Epitome of Book 63, 5:2.

- ↑ Pearse, Roger, Reference to Mithras in the Commentary of Servius? gives the sources and references.

- ↑ C.M.Daniels, "The role of the Roman army in the spread and practice of Mithraism" in John R. Hinnells (ed) Mithraic Studies: proceedings of the first International congress of Mithraic Studies Manchester university press (1975), vol. 2, p. 250: "Traditionally there are two geographical regions where Mithraism first struck root in the Roman empire: Italy and the Danube. Italy I propose to omit, as the subject needs considerable discussion, and the introduction of the cult there, as witnessed by its early dedicators, seems not to have been military. Before we turn to the Danube, however, there is one early event (rather than geographical location) which should perhaps be mentioned briefly in passing. This is the supposed arrival of the cult in Italy as a result of Pompey the Great's defeat of the Cilician pirates, who practised 'strange sacrifices of their own ... and celebrated certain secret rites, amongst which those of Mithra continue to the present time, having been first instituted by them'. Suffice it to say that there is neither archaeological nor allied evidence for the arrival of Mithraism in the West at that time, nor is there any ancient literary reference, either contemporary or later. If anything, Plutarch's mention carefully omits making the point that the cult was introduced into Italy at that time or by the pirates."

- ↑ Porphyry, On the Cave of the Nymphs, 6: "For according to Eubulus, Zoroaster first of all among the neighbouring mountains of Persia, consecrated a natural cave, florid and watered with fountains, in honour of Mithras the father of all things: a cave in the opinion of Zoroaster bearing a resemblance of the world fabricated by Mithras. But the things contained in the cavern, being disposed by certain intervals, according to symmetry and order, were symbols of the elements and climates of the world."

- ↑ Turcan, Robert, Mithras Platonicus, Leiden, 1975, via Beck, R. Merkelbach's Mithras p. 301-2.

- ↑ Beck, R. Merkelbach's Mithras p. 308 n. 37.

- ↑ Beck, R. "Merkelbach's Mithras" in Phoenix 41.3 (1987) p. 298.

- ↑ John R. Hinnells, "Reflections on the bull-slaying scene" in Mithraic studies, vol. 2, p. 303-4: "Nevertheless we would not be justified in swinging to the opposite extreme from Cumont and Campbell and denying all connection between Mithraism and Iran."

- ↑ John R. Hinnells, "Reflections on the bull-slaying scene" in Mithraic studies, vol. 2, p. 303-4: "Since Cumont's reconstruction of the theology underlying the reliefs in terms of the Zoroastrian myth of creation depends upon the symbolic expression of the conflict of good and evil, we must now conclude that his reconstruction simply will not stand. It receives no support from the Iranian material and is in fact in conflict with the ideas of that tradition as they are represented in the extant texts. Above all, it is a theoretical reconstruction which does not accord with the actual Roman iconography. What, then, do the reliefs depict? And how can we proceed in any study of Mithraism? I would accept with R. Gordon that Mithraic scholars must in future start with the Roman evidence, not by outlining Zoroastrian myths and then making the Roman iconography fit that scheme. ... Unless we discover Euboulus' history of Mithraism we are never likely to have conclusive proof for any theory. Perhaps all that can be hoped for is a theory which is in accordance with the evidence and commends itself by (mere) plausibility."

- ↑ John R. Hinnells, "Reflections on the bull-slaying scene" in Mithraic studies, vol. 2, p. 292: "Indeed, one can go further and say that the portrayal of Mithras given by Cumont is not merely unsupported by Iranian texts but is actually in serious conflict with known Iranian theology. Cumont reconstructs a primordial life of the god on earth, but such a concept is unthinkable in terms of known, specifically Zoroastrian, Iranian thought where the gods never, and apparently never could, live on earth. To interpret Roman Mithraism in terms of Zoroastrian thought and to argue for an earthly life of the god is to combine irreconcilables. If it is believed that Mithras had a primordial life on earth, then the concept of the god has changed so fundamentally that the Iranian background has become virtually irrelevant."

- ↑ R.L.Gordon, "Franz Cumont and the doctrines of Mithraism" in John R. Hinnells, Mithraic studies, vol. 1, p. 215 f

- ↑ Boyce, Mary (2001). "Mithra the King and Varuna the Master". Festschrift für Helmut Humbach zum 80 (Trier: WWT). pp. 243,n.18

- ↑ Beck, Roger B. (2004). Beck on Mithraism: Collected Works With New Essays. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0754640817., p. 28: "Since the 1970s scholars of western Mithraism have generally agreed that Cumont's master narrative of east-west transfer is unsustainable;" although he adds that "recent trends in the scholarship on Iranian religion, by modifying the picture of that religion prior to the birth of the western mysteries, now render a revised Cumontian scenario of east-west transfer and continuities now viable."

- ↑ Martin, Luther H. (2004). "Foreword". in Beck, Roger B. (2004). Beck on Mithraism: Collected Works With New Essays. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0754640817., p. xiv.

- ↑ Beck, R., 2002: "Discontinuity’s weaker form of argument postulates re-invention among and for the denizens of the Roman empire (or certain sections thereof), but re-invention by a person or persons of some familiarity with Iranian religion in a form current on its western margins in the first century CE. Merkelbach (1984: pp. 75-7), expanding on a suggestion of M.P. Nilsson, proposes such a founder from eastern Anatolia, working in court circles in Rome. So does Beck 1998, with special focus on the dynasty of Commagene (see above). Jakobs 1999 proposes a similar scenario."

- ↑ Reinhold Merkelbach, Mithras, Konigstein, 1984, ch. 75-7

- ↑ Beck, R., "Merkelbach's Mithras", p. 304, 306.

- ↑ Lewis M. Hopfe, "Archaeological indications on the origins of Roman Mithraism", in Lewis M. Hopfe (ed). Uncovering ancient stones: essays in memory of H. Neil Richardson, Eisenbrauns (1994), pp. 147-158. p.156:"Beyond these three Mithraea [in Syria and Palestine], there are only a handful of objects from Syria that may be identified with Mithraism. Archaeological evidence of Mithraism in Syria is therefore in marked contrast to the abundance of Mithraea and materials that have been located in the rest of the Roman Empire. Both the frequency and the quality of Mith-raic materials is greater in the rest of the empire. Even on the western frontier in Britain, archaeology has produced rich Mithraic materials, such as those found at Walbrook. If one accepts Cumont's theory that Mithraism began in Iran, moved west through Babylon to Asia Minor, and then to Rome, one would expect that the religion left its traces in those locations. Instead, archaeology indicates that Roman Mithraism had its epicenter in Rome. Wherever its ultimate place of origin may have been, the fully developed religion known as Mithraism seems to have begun in Rome and been carried to Syria by soldiers and merchants. None of the Mithraic materials or temples in Roman Syria except the Commagene sculpture bears any date earlier than the late first or early second century. [30. Mithras, identified with a Phrygian cap and the nimbus about his head, is depicted in colossal statuary erected by King Antiochus I of Commagene, 69-34 B.C.. (see Vermaseren, CIMRM 1.53-56). However, there are no other literary or archaeological evidences to indicate that the cult of Mithras as it was known among the Romans in the second to fourth centuries A.D. was practiced in Commagene]. While little can be proved from silence, it seems that the relative lack of archaeological evidence from Roman Syria would argue against the traditional theories for the origins of Mithraism."

- ↑ Ulansey, D., The origins of the Mithraic mysteries", p. 77f.

- ↑ Ware, James R.; Kent, Roland G. (1924). "The Old Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 55: 52. doi:10.2307/283007. http://jstor.org/stable/283007. pp. 52–61.

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L. (1978). "The date and significance of CIMRM 593 (British Museum, Townley Collection". Journal of Mithraic Studies II: 148–174.. pp.150-151: "The first important expansion of the mysteries in the Empire seems to have occurred relatively rapidly late in the reign of Antoninus Pius and under Marcus Aurelius (9) . By that date, it is clear, the mysteries were fully institutionalised and capable of relatively stereotyped self-reproduction through the medium of an agreed, and highly complex, symbolic system reduced in iconography and architecture to a readable set of 'signs'. Yet we have good reason to believe that the establishment of at least some of those signs is to be dated at least as early as the Flavian period or in the very earliest years of the second century. Beyond that we cannot go..."

- ↑ Beck, R., Merkelbach's Mithras, p.299; Clauss, R., The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 25: "... the astonishing spread of the cult in the later second and early third centuries AD ... This extraordinary expansion, documented by the archaeological monuments..."

- ↑ Clauss, R., The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 25, referring to Porphyry, De Abstinentia, 2.56 and 4.16.3 (for Pallas) and De antro nympharum 6 (for Euboulus and his history).

- ↑ Loeb, D. Magie (1932). Scriptores Historiae Augustae: Commodus. pp. IX.6: Sacra Mithriaca homicidio vero polluit, cum illic aliquid ad speciem timoris vel dici vel fingi soleat "He desecrated the rites of Mithras with actual murder, although it was customary in them merely to say or pretend something that would produce an impression of terror".

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 24: "The cult of Mithras never became one of those supported by the state with public funds, and was never admitted to the official list of festivals celebrated by the state and army - at any rate as far as the latter is known to us from the Feriale Duranum, the religious calendar of the units at Dura-Europos in Coele Syria;" [where there was a Mithraeum] "the same is true of all the other mystery cults too." He adds that at the individual level, various individuals did hold roles both in the state cults and the priesthood of Mithras.

- ↑ Beck, R., Merkelbach's Mithras, p. 299.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 29-30: "Mithras also found a place in the 'pagan revival' that occurred, particularly in the western empire, in the latter half of the fourth century AD. For a brief period, especially in Rome, the cult enjoyed, along with others, a last efflorescence, for which we have evidence from among the highest circles of the senatorial order. One of these senators was Rufius Caeionius Sabinus, who in 377 dedicated an altar" to a long list of gods including Mithras.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.171.

- ↑ Cumont, Franz (1903). McCormack, Thomas J. (trans.). ed. The Mysteries of Mithra. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 0486203239. pp. 206: "A few clandestine conventicles may, with stubborn persistence, have been held in the subterranean retreats of the palaces. The cult of the Persian god possibly existed as late as the fifth century in certain remote cantons of the Alps and the Vosges. For example, devotion to the Mithraic rites long persisted in the tribe of the Anauni, masters of a flourishing valley, of which a narrow defile closed the mouth." This is unreferenced; but the French text in Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mithra tom. 1, p. 348 has a footnote. The French text is referenced and discussed by Roger Pearse, Cumont on the end of the cult of Mithras which translates it and discusses the sources which are too long to include here.

- ↑ David Ulansey, The origins of the Mithraic mysteries, p. 6: "Although the iconography of the cult varied a great deal from temple to temple, there is one element of the cult's iconography which was present in essentially the same form in every mithraeum and which, moreover, was clearly of the utmost importance to the cult's ideology; namely the so-called tauroctony, or bull-slaying scene, in which the god Mithras, accompanied by a series of other figures, is depicted in the act of killing the bull."

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.77.

- ↑ Clauss, M. The Roman cult of Mithras, p.98-9. An image search for "tauroctony" will show many examples of the variations.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.74.

- ↑ J. R. Hinnells, "The Iconography of Cautes and Cautopates: the Data," Journal of Mithraic Studies 1, 1976, pp. 36-67. See also William W. Malandra, Cautes and Cautopates Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ↑ The Greater [Bundahishn] IV.19-20: "19. He let loose Greed, Needfulness, [Pestilence,] Disease, Hunger, Illness, Vice and Lethargy on the body of , Gav' and Gayomard. 20. Before his coming to the 'Gav', Ohrmazd gave the healing Cannabis, which is what one calls 'banj', to the' Gav' to eat, and rubbed it before her eyes, so that her discomfort, owing to smiting, [sin] and injury, might decrease; she immediately became feeble and ill, her milk dried up, and she passed away."

- ↑ Hinnels, John R.. "Reflections on the bull-slaying scene". Mithraic Studies: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Mithraic Studies. Manchester UP. pp. II.290–312., p. 291

- ↑ Ulansey, David (1989). The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195054024. (1991 revised edition)

- ↑ Porphyry, De Antro nympharum 10: "Since, however, a cavern is an image and symbol of the world..."

- ↑ Porphyry, De antro nympharum 2: "For, as Eubulus says, Zoroaster was the first who consecrated in the neighbouring mountains of Persia, a spontaneously produced cave, florid, and having fountains, in honour of Mithra, the maker and father of all things; |12 a cave, according to Zoroaster, bearing a resemblance of the world, which was fabricated by Mithra. But the things contained in the cavern being arranged according to commensurate intervals, were symbols of the mundane elements and climates.

- ↑ Lewis M. Hopfe, "Archaeological indications on the origins of Roman Mithraism", in Lewis M. Hopfe (ed). Uncovering ancient stones: essays in memory of H. Neil Richardson, Eisenbrauns (1994), pp. 147-158, p.154

- ↑ Beck, Roger, "Astral Symbolism in the Tauroctony: A statistical demonstration of the Extreme Improbability of Unintended Coincidence in the Selection of Elements in the Composition" in Beck on Mithraism: collected works with new essays" (2004), p. 257.

- ↑ Beck, Roger, "The Rise and Fall of Astral Identifications of the Tauroctonous Mithras" in Beck on Mithraism: collected works with new essays" (2004), p. 236.

- ↑ Ulansey, D., The origins of the Mithraic mysteries", p. 25-39.

- ↑ Michael P. Speidel, Mithras-Orion: Greek Hero and Roman Army God, Brill Academic Publishers (August 1997), ISBN 109004060553

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Beck, Roger, "In the place of the lion: Mithras in the tauroctony" in Beck on Mithraism: collected works with new essays" (2004), p. 270-276.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Beck, Roger, "In the Place of the Lion: Mithras in the Tauroctony" in Beck on Mithraism: collected works with new essays" (2004), p. 286-287].

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Beck, Roger (2007). The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199216134., p. 27-28.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 von Gall, Hubertus, "The Lion-headed and the Human-headed God in the Mithraic Mysteries," in Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin ed. Études mithriaques, 1978, pp. 511

- ↑ Jackson, Howard M., "The Meaning and Function of the Leontocephaline in Roman Mithraism" in Numen, Vol. 32, Fasc. 1 (Jul., 1985), pp. 17-45

- ↑ Beck, R, Beck on Mithraism, pp. 194

- ↑ J. Lebegue, "Une inscription mithriaque du musée de Pesaro", Revue archaeologique, 3rd series, t. 14, pp. 64-9, 1889. See also blog post with inscription, translation, and summary of Lebegue's argument.

- ↑ Meyer, Marvin W. (1976) The "Mithras Liturgy".

- ↑ Francis, E.D. (1971). Hinnells, John R.. ed. “Mithraic graffiti from Dura-Europos,” in Mithraic Studies, vol. 2. Manchester University Press. pp. 424–445.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.115.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.43.

- ↑ Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Harvard University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0674033876.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.49.

- ↑ Price S & Kearns E, Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion, p.568.

- ↑ Beck, Roger (2007). The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199216134., p. 85-87.

- ↑ "Beck on Mithraism", p. 16

- ↑ Hinnells, John R., ed (1971). “Mithraic Studies, vol. 2. Manchester University Press. plate 25

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.139.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, pages 26 and 27.

- ↑ Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0674033876.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.xxi.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.73.

- ↑ Price S & Kearns E, Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion, p.493.

- ↑ Price S & Kearns E, Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion, p.355.

- ↑ Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.102. The Suda reference given is 3: 394, M 1045 Adler.

- ↑ Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.102. The Gregory reference given is to Oratio 4. 70.

- ↑ Jerome, Letters 107, ch. 2 (To Laeta)

- ↑ M.Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.132-133

- ↑ M.Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.133-138

- ↑ Clauss, Manfred (1990). "Die sieben Grade des Mithras-Kultes". ZPE 82: 183–194.

- ↑ Griffiths, Alison. "Mithraism in the private and public lives of 4th-c. senators in Rome". EJMS. http://www.uhu.es/ejms/Papers/Volume1Papers/ABGMS.DOC

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.103.

- ↑ M. Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 42: "That the hand-shaken might make their vows joyfully forever"

- ↑ M. Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p. 105: "the followers of Mithras were the 'initiates of the theft of the bull, united by the handshake of the illustrious father." (Err. prof. relig. 5.2)

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 "Beck on Mithraism", pp. 288-289

- ↑ Beck, Roger (2000). "Ritual, Myth, Doctrine, and Initiation in the Mysteries of Mithras: New Evidence from a Cult Vessel". The Journal of Roman Studies 90 (90): 145–180. doi:10.2307/300205. http://jstor.org/stable/300205.

- ↑ Merkelbach, Reinhold (1995). "Das Mainzer Mithrasgefäß". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (108): 1–6.

- ↑ Martin, Luther H. (2004). "Ritual Competence and Mithraic Ritual". in Wilson, Brian C. (2004). Religion as a human capacity: a festschrift in honor of E. Thomas Lawson. BRILL., p. 257

- ↑ Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.62-101.

- ↑ Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.33.

- ↑ David, Jonathan (2000). "The Exclusion of Women in the Mithraic Mysteries: Ancient or Modern?". Numen 47 (2): 121–141. doi:10.1163/156852700511469., at p. 121.

- ↑ Clauss, The Roman cult of Mithras, p.39.

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.144-145: "Justin's charge does at least make clear that Mithraic commandments did exist."

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.144, referencing Caesares 336C in the translation of W.C.Wright. Hermes addresses Julian: "As for you . . . , I have granted you to know Mithras the Father. Keep his commandments, thus securing for yourself an anchor-cable and safe mooring all through your life, and, when you must leave the world, having every confidence that the god who guides you will be kindly disposed."

- ↑ Tertullian, De Corona Militis, 15.3

- ↑ Clauss, M., The Roman cult of Mithras, p.158.

- ↑ Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Harvard University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0674033876.

- ↑ Justin Martyr, First Apology, ch. 66: "For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them; that Jesus took bread, and when He had given thanks, said, "This do ye in remembrance of Me, this is My body; "and that, after the same manner, having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, "This is My blood; "and gave it to them alone. Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn."

- ↑ Renan, E., Marc-Aurele et la fin du monde antique. Paris, 1882, p. 579: "On peut dire que, si le christianisme eût été arrêté dans sa croissance par quelque maladie mortelle, le monde eût été mithriaste."

- ↑ Edwin M. Yamauchi cited in Lee Strobel, The Case for the Real Jesus, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007, p.175

Further reading

- Beck, Roger, "The Mysteries of Mithras: A New Account of Their Genesis," Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 88, 1998 (1998) , pp. 115–128.

- Beck, Roger, "Mithraism since Franz Cumont," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, II.17.4, 1984, pp. 2002–115. Important summary of the changes to Mithras scholarship.

- Clauss, Manfred, The Roman cult of Mithras: the god and his mysteries, Translated by Richard Gordon. New York: Routledge, 2000. Pp. 198. ISBN 0-415-92977-6 here. An excellent concise view of the current consensus.

- Cumont, Franz, Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux Mystères de Mithra : pub. avec une introduction critique, 2 vols. 1894-6. Vol. 1 is an introduction, now obsolete. Vol. 2 is a collection of primary data, online at Archive.org here, and still of some value.

- Gordon, Richard, Frequently asked questions about the cult of Mithras. Some common misconceptions, and the comments of a professional Mithras scholar.

- Hinnells, John (ed.), Proceedings of The First International Congress of Mithraic Studies, Manchester University Press (1975).

- Turcan, Robert, Mithra et le mithriacisme, Paris, 2000. Academic study.

- Ulansey, David, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World, Oxford University Press, 1989. An influential but non-mainstream account.

- Vermaseren, M.J., Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff, 1956, 2 vols. The standard collection of Mithraic reliefs.

External links

- The Electronic Journal of Mithraic Studies Academic site.

- Mithraeum A website with a collection of monuments and bibliography about Mithraism.

- L'Ecole Initiative: Alison Griffith, 1996. "Mithraism" A brief overview with bibliography.

- Cumont, "The Mysteries Of Mithra" Old English translation of obsolete intro to his book.

- Mithras: literary references Collection of primary source references to Mithras in ancient texts.

- David Ulansey's article "The Cosmic Mysteries of Mithras" from Biblical Archaeology Review, summarizing his book The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

- Google Maps: Map of the locations of Mithraea